Year by year, the land was becoming less able to provide enough food for the increasing population. Concerns grew in Europe, Asia, Australia and America at the beginning of the 20th century, fuelled by the British chemist William Crookes, who maintained in his famous speech of 1898 that: England and all civilized nations stand in deadly peril of not having enough to eat.

Throughout the centuries, natural fertilizers had been the most important means of increasing crops, but supplies of natural fertilizers depend again on the supply of animal feed – animals need to eat in order to produce manure.

Saved by bird droppings – for the time being

Natural potassium nitrate from guano – extensive deposits of bird manure found in Chile – had provided a significant supply of fertilizer for some time, also in Europe. But calculations were able to show with reasonable accuracy when these supplies would run out.

The main source of ammonia in the early 20th century was the nitrogen-rich gases released in coke production. Countries with coal industries were able to produce ammonium sulphate. Still, there was concern that this would not be sufficient to meet the needs of agriculture and the world’s food supply.

Important technical improvements had already been made to agricultural practices. At the same time, medical advances led to population growth and longer life spans. In Europe, the problem was tangible. Emigration to America reached its highest level at the turn of the century.

Air provides answer

The world could still be saved, William Crookes had said, if nitrogen could be added to the soil. Nitrogen is abundant in the atmosphere. The task was to find out how to produce large quantities at a reasonable cost.

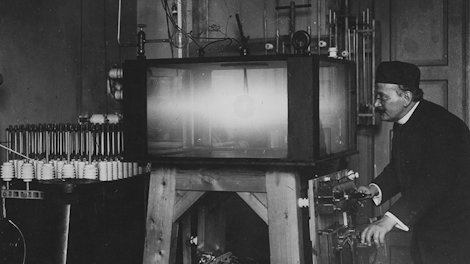

In his speech, William Crookes indicated where the answer was to be found. Passing a strong electric current between two poles causes the air to catch fire, producing nitrous gases, which contain bound nitrogen.

Power from the Niagara Falls

Many people became interested in this question from both a theoretical and an industrial point of view. An intense technological competition arose, and a number of patents were taken out in several countries. Two Americans, Bradley and Lovejoy, together with the company Atmospheric Products Co., developed a method they believed would be successful at the Niagara Falls in the U.S.

However, although they had access to inexpensive hydroelectric power, the method didn’t work as planned. Their equipment was damaged after a short time, and by 1904 they had given up.

Germany enters the race

There was widespread work in Germany to find a practical solution. In 1903, Professor Frank revealed that he had produced nitrogen compounds from calcium carbide. The resulting product, calcium cyanamide, contained around 20 per cent nitrogen, and could be used as fertilizer.

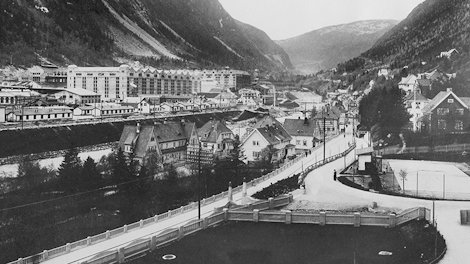

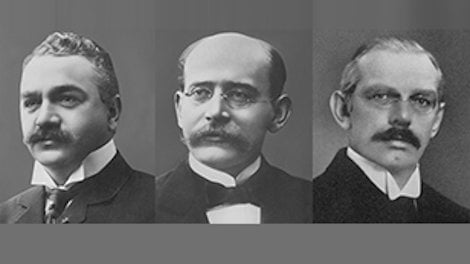

One of the German companies that started working on arc technology after 1898 was BASF (Badische), under the leadership of the chemist Otto Schönherr and the electrical engineer Johannes Hessberger. Progress was slow, and sometimes the work stopped altogether. In the autumn of 1903, Badische was contacted by a Norwegian engineer, Sam Eyde. This seemed to lead to renewed efforts on a broad front to find the best technology for extracting nitrogen from the air. The articles “Explosive winter days in 1903” and “A project of caliber” illustrate the connection. The inquiries by Eyde were no coincidence. There was someone in Norway – a poor country at the time in a union with Sweden – who was trying to come up with the invention that Crookes had said would be epoch-making for mankind’s progress.

Updated: August 17, 2020